FIFTY YEARS ON AND STILL NOTHING SO APPALLING IN THE ANNALS OF HORROR

A Cultural Review

by

Dom Salemi

October, the month of mellow fruitfulness, wherein we watch with delighted gaze, autumn falling softly into winter. Trees are a riot of color: Halloween orange, fire engine red, honey yellow. The mums are in full bloom, and the air possesses a crisp mellow feel one can almost taste. Yes, ripeness is all – but is it? For with ripeness quickly comes rot, barren skies and a suddenly denuded landscape. Worse yet, Thanksgiving, where under the guise of blood bonding old wounds are opened, long-festering quarrels erupt, and madness freely perambulates about the ancestral manse. Truly, when one stops and reflects, there is little to be thankful for at this time of year. So, to add to your burgeoning angst, we humbly offer this treatise so as to accelerate the loosening of your raveled sleeve of care.

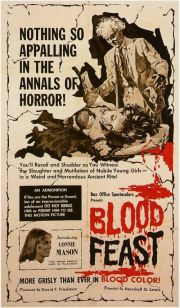

BLOOD FEAST – (d) H. G. Lewis (1963)

By now, almost every gorehound and sleaze aficionado knows the story of frenzied Fuad, the crazed caterer who slices, dices and savages young women in an attempt to accurately recreate a five thousand year old Egyptian feast and, in the process, bring to life, Ishtar, an equally antiquated Egyptian love goddess. This writer, however, would bet his house and lot that most readers of this most excellent cultural Internet site have never heard of this film.

Blood Feast was shot on the cheap in about a week and had its premiere at an Illinois drive-in. From that inauspicious debut, this impoverished exercise went on to make millions and, over time, to become one of the most influential and revered films in the horror field.

What most cineastes don’t know, and that includes pundits of the putrescent, is that H.G. Lewis and his co-conspirator, David Friedman, believed Blood Feast to be little more than junk and had no idea that it would go on to be so successful. “Everyone was surprised at the business the picture did, including myself,” director Lewis opined at an interview given in 1975. “There were many people who wanted their money back. There were many people who saw it five or six times, which bewilders me, because I’d never call Blood Feast a good production.”

In an ironic twist of fate, both writer-director Lewis and producer Friedman ended up making very little money from the film. Friedman, having little faith in the work, sold all his rights early on, and Lewis lost his in a lawsuit. Poetic justice, perhaps, for two filmmakers who had little love for a film they considered “a shoddy piece of crap.”

Whatever personal reservations the duo had about Blood Feast, Friedman and Lewis had to be proud of the controversy they engendered. Friedman maintains, with no small measure of pride, that Blood Feast was one of the most maligned pictures in the history of cinema. Certainly the reviews of the film support his contention:

“Totally Inept Horror Shocker,” screamed Variety’s headline in its May, 6, 1964 issue. The review that followed was even less kind: “ . . . incredibly crude and unprofessional from start to finish . . . is an insult to even the most puerile and salacious audiences . . . a fiasco in all departments.”

“Blood Feast is grisly, boring movie trash,” announced the LA Times.” “A blot on the American film industry . . . an insult to all but readers of horror comic books.”

“Amateur night in the butcher shop,” shrieked the New York Times.

Critics, as they so often do when shocked by the new, got it wrong. Blood Feast is such a sublime work of anomie and contempt that only a philistine would fail to recognize its singular brilliance. It is the world seen through the eyes of a homicidal and psychotic child.

Still, it is not merely the highly original depiction of misogynistic mayhem which amuses and engages. There is the rapturous and lyrical disdain suffusing every frame of the film, a disdain which reaches absurdist heights in the celebrated “lamb’s tongue” sequence.

Normally, even in today’s torture porn displays, a scene involving a tongue extraction would last only a few moments. In Blood Feast it goes on for what seems like forever. Moreover, it is filmed as an erotic, languorous danse macabre. When our pneumatic young lovely is assaulted, she does not frantically fight for survival as one would expect. Instead, she allows herself to be gently pushed on the bed and mounted by the madman. Once this has been effected, the lunatic, even more gently, corkscrews two fingers between his prey’s eager and moistened lips. He then apes coitus while forcefully tugging on the tongue. All this while our now clearly aroused victim moans and whimpers. When the monstrously elongated tongue is finally uprooted, there is no cutting away, the viewer is asked to studiously gaze at the spuming, mutilated mouth of the dying woman. Dying with a dying fall.

This is not the disdain, or contempt of a timid, trivial soul. No! It is a marvelous, sublime disdain. A profound disdain, a preternatural loathing, really, one that manifests itself, not just in the aforementioned scene, but throughout the film. For the actors in forcing them to recite humiliatingly dreadful lines, and to perform with dime-store props and a rotting lamb’s tongue. For the notion of filmmaking as craft by refusing to recognize even the most elementary aspects of the discipline. And, finally, for the audience by imagining the men and women in it to be little more than cretinous swine with appetites so brutally atavistic that satiation can only be achieved by a direct appeal to their most depraved and secret desires.

This is the ultimate triumph of Blood Feast: it is a work that exists solely and only for itself. Like DuChamp’s urinal turned on its side, it is perfection as it is, at once, art and anti-art and so does not admit criticism. This supernal quality makes Blood Feast one of the supreme gestures of revulsion in modern art. More celebrated works in this vein, such as Ezra Pound’s Hugh Selwyn Mauberly, or T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land simply cannot begin to approach Lewis and Friedman’s achievement. Accidental though that may be.

Yet perhaps the greatest relevance to you, dear reader, is that the bourgeois parvenu to whom you are presently handcuffed will also be found incapable of approaching Blood Feast. Nevertheless, screen the film for this provincial dilettante, then argue passionately and loudly about its singular importance in the field of modern art. You will be derided, labeled asinine, and, in the end, held to be insane. No matter. Your inconsequential affair will end, and the shackles of an impoverished and intellectually bankrupt relationship will be removed, leaving you free, free at last, to trod your own path to enlightenment . . .