The Construction of Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B

A very personal and technical written and photographic history, by James MacLaren.

Page 4: Introductory Background Page 4 of 5 - Entering the Pad.

| Pad B Stories - Table of Contents |

And now let us get introduced to our new job. Let us get introduced to our new launch pad.

Let us get introduced to the place where we now, still-disbelievingly, find ourselves at work. Find ourselves getting paid to walk around in slack-jawed amazement on one of the crown jewels of Western Civilization's technological achievement, every single day.

Richard Walls, my boss, became as a second father to me, saw the light in my eyes, and with scarcely-believable grace and forbearance, sought to feed the flames of that light, by doing his utmost to feed me a steady diet of knowledge.

And I wanted to know everything.

And he did his dead-level best to show me, and to teach me... everything. I shall never repay the debt, and in fact, this series of photo-essays is yet another installment in my life's work to somehow pay it back by paying it forward.

I was an answering machine, but when RW was in the trailer he could answer the phone for himself, and when that was the case, as it was often, there was no need for an answering machine.

And impossibly, he would simply let me go.

He would tell me that I would need to be back after this many minutes, or that many hours, and send me out the door!

From most locations up on the pad, Sheffield's field trailer, with Dick Walls' car parked out in front of it, was either directly visible, or just a few short steps away from being visible, and I would always check periodically to make sure his car was still there, and if, every once in a while, it was gone because Dick had been unexpectedly called away to some thing, some where, I would hotfoot it back down off the pad, back to the trailer, back to the telephone, and we never encountered a single issue with me being out of the trailer, in all the time I was an answering machine. RW trusted me, and I was very careful to live up to that trust, unfailingly.

And so I would bound down the steps, and off to the launch pad I would go, with more gratitude and glee in my heart than can ever be described.

RW trusted me to A.) Not get in anybody's way, and B.) Not kill myself by running afoul of any of the too-many subtle and extraordinarily-dangerous things in this heavy-construction environment there are to sensibly count. And I was as faithful to that pair of premises as I possibly could be.

And somehow, that glee, and that gratitude, must have been coming out of the pores of my skin in a way that everybody could see it, because everybody else out on the pad seemed to share in my enthusiasm, and seemed to want me to understand what they were doing.

They wanted me to know.

And I found myself in the company of Union Ironworkers, a rougher group of people you would be hard-pressed to find anywhere in the world, and they took me under their wing.

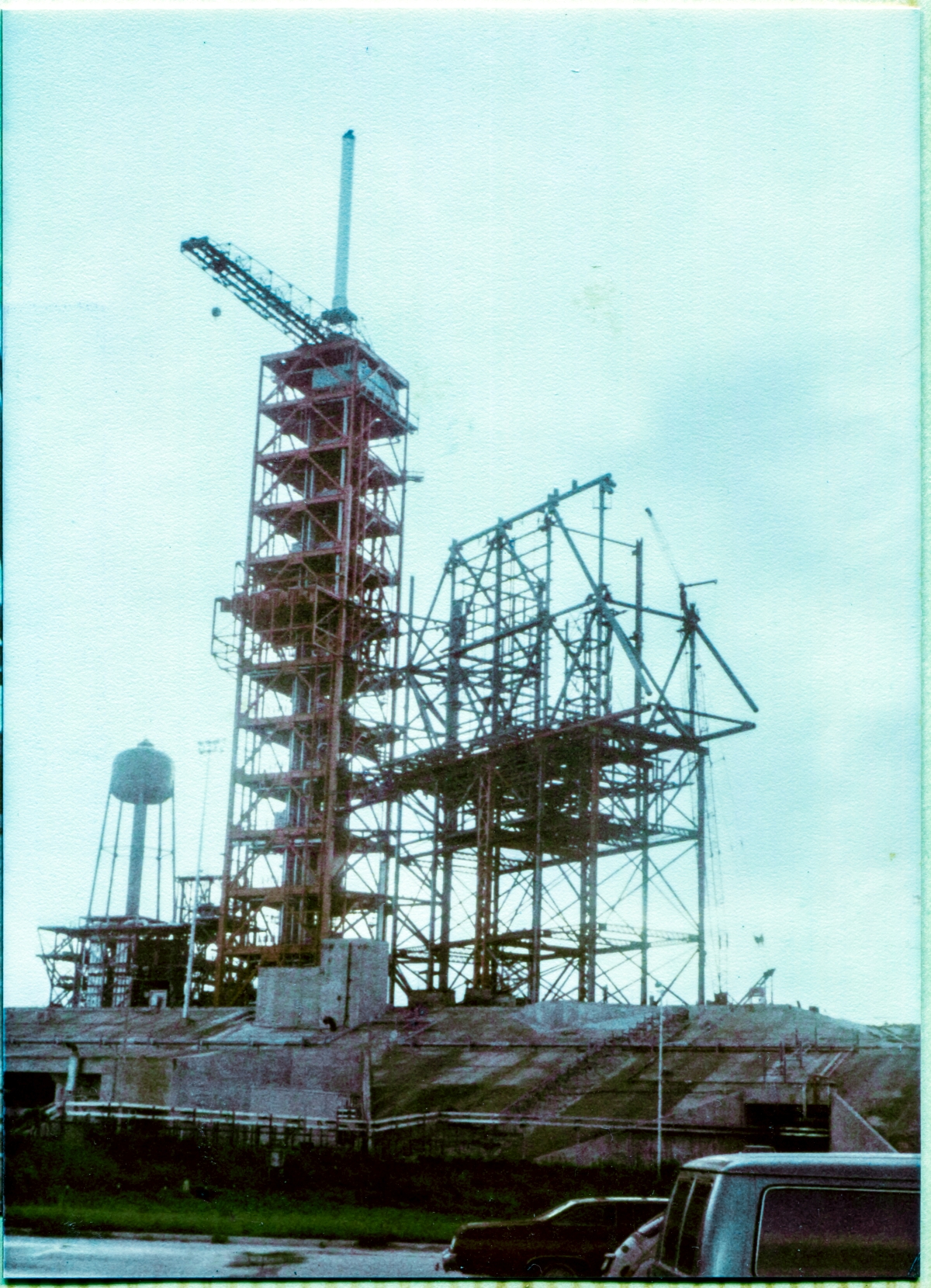

In the image above, at bottom right, you're seeing a part of Tom Kirby's green van, and beyond it, my own ratty little yellow VW beetle with a Fred Flintstone rusted-out floor pan. Literal holes you could see the road through, as you drove. I was dirt-poor, but somehow it never bothered me in the slightest. Never noticed it at all.

Tom Kirby was Wilhoit Steel Erectors site boss, working directly under Cecil Wilhoit (who founded the company) at the pad, running a gigantic project with a very large crew of ironworkers erecting the colossal steel skeletons you see on top of the pad in the distance.

Tom was a gruff old man. Brooked neither shit, nor so much as a single wasted minute of his time, from anybody. Ex-ironworker. Tough as nails.

And somehow, by some miracle, this skinny uneducated clueless surfbum somehow fell in with Tom and everybody else at Wilhoit, too.

Ironworkers are not known for their softness nor their warmth.

And yet....

Somehow....

And Wilhoit's general foreman, Red Milliken (I can only hope I'm spelling that name right, and while we're at it here, I must warn you I'm prosopagnosic. I am significantly handicapped with facial recognition, and my disability extends into name recognition, too.) also decided that I was a thing to be tolerated. A thing to be helped occasionally. And Wilhoit's ironworkers and ironworker foremen, too. Elmo McBee. Junior Hilton. Paul Hill. Tommy Ellis. Ray Elkins. All of them. My disability has destroyed recollection of too many of their names, alas. But I recall the people. I recall the humans. The weathered faces, the voices, the soft-spoken easy-drawling language, the mannerisms, the mostly purposeful but on occasion astoundingly relaxed languid and casual steps above paralyzingly-fearsome life-taking drops yawning beneath narrow spans of high steel, the denim work clothing and scuffed boots, the stickers on their hardhats, the suspenders and the toolbelts ever-clanking with the sound of hanging spud wrenches, the cigarettes and chewing tobacco, the anger, the laughter, the exasperation, the stories told with twinkling eyes and sly half-smiles, the stoic resignation, the steely-eyed grit and determination, allofit. With tack-sharp clear vision, I recall these people. And they were, one and all, Good People. And they were, one and all, good to me.

I shall never understand the least of it. Never in a million years.

You are reading this because you want to know how the launch pad works.

You are reading this because you want to know how things work and how things happen.

And I can only tell you how things work by telling you about the things that happened to me.

I wish I could tell you more, but alas I cannot.

I can only tell you how things happened to me and who they happened to me with.

Out the door and up to the pad.

On foot. Almost always. It wasn't that far. And I was a skilled surfer, having only a few years earlier returned from four complete Winter Seasons on the North Shore of Oahu, doing this sort of thing, and as anybody who's attempted it can well attest, proper surfing on large waves is an insanely-difficult full-aerobic workout, which will kill you if you let it, which meant that I was very healthy, and I viewed the walk up to the Pad Deck as a quite enjoyable and fun thing to do, Beneath a Florida Sky. And it was also a very dynamic construction site up there, and despite the outsize dimensions of everything, there wasn't really all that much room up there for cars, and as the New Guy I most assuredly did not want to come across as being pushy or self-serving to the least degree, and for those reasons, and more, most of my visits to the Pad Deck were on foot.

Up to the growing RSS, yellow-highlighted here in a very general way, to distinguish it, somewhat, from the overwhelming complexity of the falsework it's resting on, and the Hinge Column and Struts it's partially in front of.

Be advised that in that linked drawing, with red, blue, and green fill-colors to help you distinguish one major component from another, numerous access platforms, crossover platforms, cable trays, and the framing which supports them, are shown, none of which has yet been installed, as seen in the photograph at the top of this page. The Hinge Column and Struts are there, and the Hinge Column is a simple enough thing to perhaps locate on your own in the photograph, but the Struts are diabolically hard to pick out as distinct entities from all of the horizontal and diagonal bracing in the falsework, the diagonal members in the RSS, and the additional horizontal and diagonal structural framing members in the FSS, and all of it is flattened against a too-bright sky in the photograph to a point where very little of it can reliably be visualized, so for now, leave that be.

Reading technical drawings requires a bit of consideration, and can take a little getting used to, and I'm going to try and ease your path through this stuff as much as I can, but in no way can it all be "spoon fed" to you with any expectation of it making proper sense to you, so you must put a little of your own work into it, to get anything back out of it.

With my help, things that you can't see now, and things that don't make sense now, will become visible, and will start to make real sense, as we work our way along, in similar fashion as I had to work my own way along, with the help of Richard Walls, and Wilhoit's sterling crew of Union Ironworkers, back when this place was all so very strange, and wonderful, and bewilderingly-new to my completely untrained eyes.

The RSS needed to be able to move out of the way, to let the Space Shuttle get rolled to its location on the launch pad, from where it would take off. And after it had made room for the Shuttle by moving out of the way, it had to then move back, to a place where it could load payloads into the Space Shuttle's Cargo Bay.

All of this rationale is well-explained in a reference document I linked to back on Page 1, "MECHANICAL FEATURES OF THE SHUTTLE ROTATING SERVICE STRUCTURE," and I'm going to link to it again in cleaned-up text-only form, so we can more easily refer to it, because it's a very good description of a lot of the "why" as to the particulars of the RSS. Right here would be a really good place to stop, click that link I inserted just above these words, and read that whole article. It comes in at just under 3,000 words, and it covers an amazing amount of ground, doing an extraordinarily-good job of explaining the basic premise of the RSS, and why it needed to be the way it was.

The particulars of the RSS lead us directly to the requirement for a Hinge Column (which the document calls a "pivot column" and we've already been told how things get renamed oftentimes as a large project moves forward), and for the Struts which hold it in place, and among those particulars you can find in our referenced document the following:

"The pivot column is 42 inches outside diameter by 33 inches inside diameter. At the top of this pivot column, as shown in Figure 2, is a bearing assembly comprised of a 30 inch diameter ASTM B148 955-HT aluminum bronze hemispherical thrust bearing race rotary on a 41 inch diameter ASTM A182-304 S.S. Alloy steel thrust bearing the hemispherical ball. Just below this main support bearing is a 61 inch diameter side thrust bearing race and ball. This pivot bearing assembly has a 6 foot 2 inch diameter, A441 housing with a removable cover retained in the housing by means of a tapered shear key ring, thereby allowing for bearing changeout in the unlikely event the need should ever arise. The vertical resultant load support at this bearing assembly during rotation of the structure is in the order of 2,000,000 pounds (1,000 tons)."

Two million pounds. Just on one side alone.

Which pretty much sums up the whole RSS, right there.

Basically, what it amounts to, is that it's a thirteen-story high-rise hotel, which has been suspended sixty feet up in the air on a gigantic open-air steel framework that only touches the ground on either side of our hotel at its extreme side edges, using, on one side, a Hinge Column that has a pair of truly massive bearings, and on the other side, a pair of drive trucks which rest on a pair of curved rails, and the whole apparatus swings open and closed, in no way different from a normal door in your home swinging open and closed, except that this particular "door" spans 160 feet from its hinges to the far side of the door, stands just about 190 feet tall in overall height, and weighs over four million pounds.

The photograph at the top of this page provides our best look at certain components of the RSS that will later on be surrounded and blocked from view by the erection of additional steel and wall-siding panels, so we will take a few minutes to point them out, and perhaps advise that later on in this series of essays, we will be visiting these places again, as well as many others, describing things and events as we go.

And to get to the RSS, we must walk from our field trailer past the toe of the fifty-foot high concrete hill of the pad itself, and take the concrete stairs, from ground level, to the Pad Deck.

The notch in the outline of the great concrete mound which is the body of the pad, where you enter the pad through an insane pair of blast-resistant doors, and once inside the pad, you find yourself in the Pad Terminal Connection Room, which is actually a quite-large two-story, multi-room, facility, which you walk through to get to the place where you open the door to the stairwell which takes you to the pad deck up above, is visible in the photograph above, but it's more or less impossible to pick out because of poor lighting, resolution, and point of view behind an intervening utility building. Here's our photograph again, with the salient features highlighted and labeled, to help you see things a little better.

Here is the location of the "notch" on an overview of the entire pad. The outline of the raised portion of the pad was surprisingly intricate, and could be difficult to navigate. Which well illustrates some of the problems encountered when attempting to describe things in detail. A lot of it is there, but it's not always particularly easy to see.

Let us stop and visit the Pad Terminal Connection Room doors for a few moments, on our way up to the pad deck.

Here's another view of the whole Pad, which also contains details of the Blast Doors you walked through to get to the stairwell. Give yourself a proper look at the construction of these things, please. This is what you literally first encountered, entering the pad, on your way to work, up above the top of the pad somewhere, on high steel.

4-inch channel iron, on one-foot centers, vertical and horizontal, concrete-filled, skinned over with quarter-inch steel plate for good measure.

Holy. Shit.

This is atomic-bomb grade stuff. This is serious business stuff.

Many people can unthinkingly pass through a thing like this without giving it too much thought, aside from perhaps, "Hmm, that's kinda different-looking, isn't it?"

But other people will look at it, and then stop and consider.

Perhaps stop and consider the level of energy release that somebody was thinking might be encountered, up-close and personal, by the people and equipment on the other side of these doors, which energy release might not be such a good thing for those people and that equipment, thus necessitating the need for the doors.

And once stopped, and giving it the consideration which it is well worthy of, one might get a shiver all the way down one's spine, thinking about what it really means.

And then that shiver might run right back up your spine again all the way to the hairs on the back of your neck, when you realize that people were going to be placing themselves inside the thing that might be releasing all that energy, all at once, in a horrifically-unplanned way.

I cannot offer enough respect for the crews who flew these vehicles.

As far as I'm concerned, there is no upper bound for that respect.

The stairs to the pad deck take you to a very stoutly-constructed concrete enclosure on the pad deck, which abuts a similar enclosure for the freight-elevator, immediately to its south.

Exiting the stair through the doorway in the enclosure, the FSS towers far above you, a little to your left, and the great mass of the RSS blots out the sky right in front of you, looming almost directly over your head.

Our image at the top of this page, among many other things, is showing two separate items in the RSS that we might be interested in for our work today, the PCR Girts and the PCR Elevator Tower.

The PCR Girts on the Column Line A side of the Payload Changeout Room (which is Side 3 of the RSS, side 1 facing the Shuttle, and you go around clockwise from there) look to be finished, but over toward the Column Line 3 side of the PCR, the Hinge Column side of the PCR, (which is Side 4 of the RSS, and yes, things can get very confusing with letters and numbers, and we must always be paying close attention to things like that), the horizontal girts are more or less in place, but this is a much more complex area, and it looks as if some of the horizontal framing has yet to be erected, and a lot of the vertical framing isn't finished, and since all of this framing shows very poorly in the photograph, I'm not going to even try to highlight it on Drawing S-92 for full agreement with what's on the photograph, and instead, just give you a general idea as to what's in this area, on this side of the PCR.

The girts, which are horizontal steel members that will be holding up the wall panels, along with any required door openings, and a few other smallish things, and which will define the envelope of the Payload Changeout Room, are straightforward enough, but the elevator steel has a bit more going on with it, and in this photograph we are getting the only look we will ever get of the exposed PCR Elevator framing steel. It would very soon disappear forever behind the exterior wall panels of the elevator shaft.

On structural sheet S-45, which was used to fabricate and erect the Elevator Steel, you can see where I've highlighted only that portion of the Elevator Steel which had actually been erected when I took the photograph, and if you look close, (click on it, bring it up full-size) you can see where the highlighting on the columns stops below the level where the same highlighting on the diagonal bracing keeps going up a bit higher, and this is because structural steel shapes only come so long from the mill, and no longer, and at some point along the full vertical extent of this steel, there's going to have to be a splice, and that splice-point will be located at the top ends of the columns, as seen on the day that I took the photograph at the top of this page, and there was no need to stop the diagonals at the same place because they're all plenty short enough to not require any splice of their own, and as a result, the last set of them is full-length, and that length extends upward past the place where the next sections of the columns will be spliced on top of the existing steel that you can see in the photograph, if you look very closely at it. In addition to that, there is also, right at the tops of those columns, some very light horizontal steel tying them together rigidly, and this is placed there, temporarily, to hold those columns exactly in place, exactly where they belong, so as when the erection in this area proceeds with the splicing of the upper lengths of these columns on to the bottom lengths of the columns, things will fit, and things will fit exactly, and not so much as an extra minute of time will be wasted in getting things properly aligned for the steel which will be resting on top of that which you see in the photograph.

There will be much more to come for both of these items, including a really scary story involving the Elevator Steel, and many more other items as well, but for now, let us save that for later and be content with simply knowing that such things exist, and knowing their locations.

At the time I took this photograph, Dick Walls and I were just beginning to realize that there might be a little bit more to James MacLaren than either one of us had at first assumed, and he was just starting, to send me up on the pad for actual work, instead of letting me simply go up there on my own, as I attempted to learn where I was, and what was going on there.

Soon, very soon, my own bootprints would start appearing on high steel. Haltingly and hesitantly at first, but it was a beginning, and it was a change in direction that would take me down a very long and astounding pathway.

We are now beginning to learn about the pad in earnest.

Return to 16streets.comACRONYMS LOOK-UP PAGEContact Email Link |